In today’s world, the youth population1 is the largest it has ever been in history, accounting for 24% of the global population and yet, they are often overlooked, even though they bear far-reaching consequences of armed conflict.

In many conflict-affected countries, youth constitute the majority of the population, with estimates suggesting that nearly one in four young people are affected by armed conflict in some way2. The repercussions include impeded access to education, healthcare, and secure livelihoods, alongside recurring victimization, identity-based discrimination, and social and economic marginalization3. Therefore, it is imperative for local, national, regional and international institutions and stakeholders to devise strategies that actively engage young people in peace processes and during periods of peaceful transitions.

An important milestone for the youth, peace and security (YPS) agenda, was the adoption of the first United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR 2250) in 2015. This resolution established a global normative framework recognizing the vital contribution and role of young people in peace processes. It emphasizes the importance of including youth in peace negotiations and agreements, acknowledging that their exclusion can impede the achievement of sustainable peace4. Three years later, a second resolution highlighted the constructive role of youth in peacebuilding and conflict prevention. It urged all stakeholders to consider their perspectives and ensure their full participation in peace and decision-making processes at all levels5.

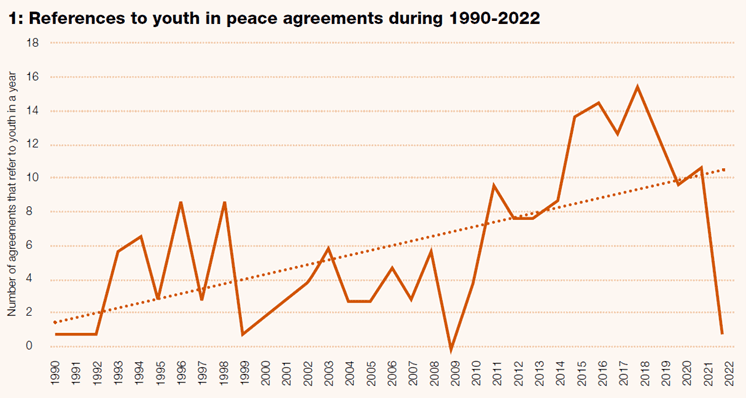

When examining the history of peace processes6, there is a notable focus on negotiations that typically involve primary stakeholders and decision-makers from conflict settings, often sidelining more inclusive processes and agreements. Consequently, young people are rarely included as active partners in peace negotiations and are often mentioned only marginally, if at all, in peace agreements. Research indicates that youth are referenced in merely 12% of peace agreements concluded between 1990-2022, with an increasing trend observed since 20107.

Ozcelik & Shaw (2023)

In recent years, there has been increasing discussion on the importance of inclusivity in peace processes, offering greater opportunities for diverse segments of society to participate directly or indirectly. Research supports this trend, highlighting how broader participation enhances the sustainability and success of peace efforts8. While there is limited research on the specific nature, impact and outcomes of youth inclusion in peace processes, Ozcelik & Shaw (2023) have made a notable contribution to this field. Their study illustrates that involving youth in negotiation processes correlates positively with achieving outcomes that are more inclusive of youth perspective. They find that such inclusion results in agreements that address youth concerns across multiple dimensions, rather than focusing narrowly on a single issue.

A positive example of effective inclusivity is that of Yemen’s youth and its pivotal role in the 2011 National Dialogue Conference (NDC) following grassroots protests. A 20% youth quota was established, resulting in forty independent, politically unaffiliated youth being selected as delegates. These youth representatives often voted as a bloc, allied with women and civil society groups, and influenced key decisions. Despite challenges like accusations of co-option, their involvement set new norms for youth political inclusion. Youth leaders facilitated technical working groups, advocated for employment and education reforms, and addressed sensitive issues, significantly impacting Yemen’s political landscape and demonstrating the value of youth participation in peace processes.9

Two important aspects stand out when analyzing mentions of youth in peace agreements: Firstly, some references are merely rhetorical and tokenistic, often grouping youth together with other categories such as women, the elderly, children, or people with disabilities, lacking substantive direction. Secondly, references to youth are prominently featured around topics such as ‹ violence & security › or ‹ unemployment › as well as various aspects of peacebuilding10. Experts stress the importance of not confining ‹ youth issues › to particular themes but rather broadening their potential impact11. Furthermore, youth groups advocate for acknowledgment of their pivotal role across diverse societal levels and demographics11.

Against this backdrop, there remains a need to reconsider the role assigned to youth in peace processes and to promote diverse forms of participation. The following recommendations can serve as entry points to enhance the role of youth in peace processes, which will be complemented by additional reflections and recommendations in this magazine:

- Integrate Youth Broadly in Peace Processes: Involve young people in a wide range of relevant topics within peace processes, not just those that directly affect them.

- Promote Positive Youth Representation: Move beyond the dominant narrative of youth as troublemakers. Represent youth in diverse and constructive ways, emphasizing their role as peacebuilders.

- Create Inclusive and Participatory Spaces: Establish inclusive and participatory spaces for youth in peace processes. Involve them from the outset in the design and implementation of these processes, incorporating context analyses that are sensitive to their experiences, concerns, and vulnerabilities.

- Conduct targeted research on youth inclusion: Undertake targeted research on youth inclusion in peace processes to enhance understanding of the factors that influence the outcomes and effectiveness of peace efforts.

[1] The UN defines the terms “youth” as persons of the age of 18-29 years old. Please note that there are multiple variations of the definition of the term which exist on the national and international levels (S/RES/2250 (2015)).

[2] Hagerty, T. (2018). Data for Youth, Peace and Security: A summary of research findings from the Institute for Economics & Peace. Sydney: Institute for Economics & Peace & UN Security Council, Resolution 2250 (2015). S/RES/2250 (2015): http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/doc/2250.

[3] The Missing Peace Progress Study, §8, A/72/761, S/2018/86

[4] UN Security Council, Resolution 2250 (2015). S/RES/2250 (2015): http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/doc/2250

[5] UN Security Council, Resolution 2419 (2018). S/RES/2419 (2018): http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/doc/2419

[6] Such as for example the Dayton Accords in 1995, the Taif Agreement that brought an end to the Lebanese Civil War in 1989 or the Sudan Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005.

[7] Ozcelik, A. & Shawq, D. (2023). References to Youth in Peace Agreements, 1990-2022, University of Glasgow. The dataset (YPAD) compiles 208 peace agreements which were concluded in the period of 1990-2022 and make an express textual reference to youth, young people, and similar. For more information on the dataset consult Ozcelik & Shaw (2023) (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TZZOEX).

[8] See for example Paffenholz, T. (2015). Broadening Participation in Political Negotiations and Implementation. Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue; Nilsson’s 2012 statistical analysis of peace agreements reached between 1989 and 2004 showed that the involvement of civil society actors reduced the risk of a peace agreement failure by 64%; see Nilsson, D. (2012) Anchoring the Peace: Civil Society Actors in Peace Accords and Durable Peace. International Interactions 38(2), 243-266.

[9] The Missing Peace Progress Study, A/72/761, S/2018/86.

[10] Ozcelik & Shaw (2023), 14.

[11] The Missing Peace Progress Study, §8, A/72/761, S/2018/86.

[12] Statement by a group of youth of the Syrian Civil Society Support in the framework of the 6th EU Brussels Conference on the future of Syria and the region: https://cssrweb.org/en/round/side-events-brussels-3/.